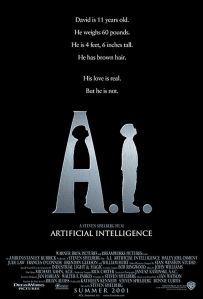

I find myself revisiting A.I. again, 8 years after it was originally released, because I’ve been skimming through a book about Stanley Kubrick this week (see farther down). I vaguely remember the excitement and trepidation of seeing the film in the theatre when it came out amongst a great deal of critical confusion (as Kubrick’s movies were usually prone to). I also remember the groundbreakingly awesome piece of viral marketing/online game that we eventually found out had absolutely nothing to do with the movie but was still awesome. I do remember watching the film in ecstatic confusion the first time, in the theatre. This is my third time seeing the film.

I find myself revisiting A.I. again, 8 years after it was originally released, because I’ve been skimming through a book about Stanley Kubrick this week (see farther down). I vaguely remember the excitement and trepidation of seeing the film in the theatre when it came out amongst a great deal of critical confusion (as Kubrick’s movies were usually prone to). I also remember the groundbreakingly awesome piece of viral marketing/online game that we eventually found out had absolutely nothing to do with the movie but was still awesome. I do remember watching the film in ecstatic confusion the first time, in the theatre. This is my third time seeing the film.

Here is a movie, planned by Kubrick for a long time, from an original story worked out in the early 1990s in collaboration with various notable sci-fi authors (since the seed of a short story by Brian Aldiss, published in 1969), that Steven Spielberg took up after his death (or perhaps as far back as Jurassic Park in 1993, when he discussed its digital effects with Kubrick at length). It is well-known that Kubrick felt the available technology was not up to the visual representation of the film he wanted in all the time he worked on the project. After seeing Jurassic Park, he apparently warmed to the idea of it as a serious future possibility. Regrettably, he missed making the film himself by a couple of years – that is assuming he would have been satisfied enough (or propelled by Warner Brothers accounts) to do it (I’ve heard stories that he actually had, among other people, Chris Cunningham building him robots that would possibly stand in for the main character of David). Maybe I’ll watch this again after Avatar comes out and brood about how Kubrick could have had late night phone conversations with James Cameron about technology….

So, we have a movie that is inevitably rooted in a cerebrally calculating style of irony and detachment that is usually attributed (perhaps in slight excess) to Kubrick, and a shooting screenplay by Spielberg (his first since Close Encounters of the Third Kind in 1977), who is equally coloured as a master craftsman, but also happens to be a sentimentalist; an emotional manipulator with severe mommy and daddy issues (i.e. E.T., Close Encounters, Empire of the Sun, Hook, etc.). So, what we get is a weird mesh of two auteurs in one movie, one in the flesh and one by (artificial) proxy.

Therein lies the first of many ironies. In the final product, in a film about the division between realness and artificiality, we have the everlasting question of what of this film belongs to Kubrick and what to Spielberg. Or in the cynical critic’s eye, what parts has Spielberg messed up and what did he add to its incompleteness?

The film is rife with all sorts of literary devices that would make Kubrick proud. The adherence to Freud is particuarly noteable. This is, after all, a film about a (robot) boy who wants more than anything to get his mother to love him above all else. The conscious decision to retain some of its ‘headiness’ is not lost on those wanting “that one more Kubirck film”; after all, Mother is reading, in the bathroom no less (a location in nearly every Kubrick film), Freud on Women, when David barges in on her in a misconstrued game of “hide-and-seek”.

There’s also the scene with all the mannequin-like robot shells, which one can assume is most certainly a nod to Killer’s Kiss (sorry, I don’t have that one for screen comparison):

<– And Spielberg doesn’t really overquote Yeats in his usual movies (Yeah, ok, I had to look it up).

As a homage to Kubick, I think the gripes against Spielberg are still vaild. While he is ‘growing’ as a filmmaker, making more ‘adult’ story decisions these days, those made during A.I. were perhaps among some of his first (Schindler’s List, of course, aside). He still frames the majority of this film though a child’s viewpoint (perhaps his own?), which would be fine if the story was written that way, but it’s not (The narrator is, as we come to find out eventually, closer to Starchild than child).

The choice to have John Williams score the film (a frequent Spielberg collaborator) overburdens the film with too much sentimentality (even in places its not needed, like when the scientists are talking in the beginning). Kubrick may not have gone the classical route ala 2001 again (it was his idea to use Ministry as the Flesh Fair band, though that was in the late 1990s when people actually still knew who they were).

The Rouge City sequences are all much morally tamer and less story crucial than anything Kubrick would even half-ass. While some argue he would be just as much of a conservative in his depictions of the ‘celebrations of life’, I would hope….well there’s no point in speculating I guess.

James Naremore put it best in his On Kubrick (which I’ve been skimming through lately) by stating that, “Throughout, the Disneyish atmosphere is inflected with an art-cinema irony” (p.269). I would just argue that it feels the other way around. I really really want to know how far Spielberg did or did not stray from whatever ending Ian Watson (Kubrick’s self-professed “mind slave“) had originally come up with. If Spielberg didn’t completely just tack on the last 20 minutes of the movie himself, he was born to direct it anyway….

There are many ways to pair down the film. For some it’s a sci-fi exploration of “artificial intelligence” as a concept and a potential reality. For some, it’s a postmodernly, self-conscious update of Pinocchio (and a bit of Oedipus). For some, it’s slightly political apocalypse allegory, warning us into the environmental climate change that will do us all in and the technology we depend upon overrunning our human utility and purpose. I’d like to think it’s all of those and more. For the mess of a film that it is, it still more captivating than any other studio-gestating sci-fi of recent memory.

I’m not sure what I was intending when I sat down to write about this film. There’s too much to cover and not enough brain power (at the moment) to even scratch the surface. For as much as I remembered (which is a testament to the filmmaking I suppose), there was a lot to it that I had forgotten. I wasn’t as in awe this time, but there was definitely more than enough to think about (again). It posits several core ideas throughout the film:

1.

“FEMALE TEAM MEMBER

“FEMALE TEAM MEMBER

But you haven’t answered my question. If a robot could genuinely love a person, what responsibility does that person hold toward that mecha in return? It’s a moral question, isn’t it?

PROFESSOR HOBBY

The oldest one of all. But in the beginning, didn’t God create Adam to love him?”

What is the nature of man’s relationship to the world? In all our seeming dominance of the planet, are we really in control? And if so, how do we protect ourselves from our own control? The idea of God does not reach beyond Its so-called power and glory. We explain away the lack of control over our species as a gift (of free will), but in giving that to our own creations (of artificial intelligence), we would attempt to deny this free will, while also expecting love; the idea of love programmed to extrapolate from some pre-conceived algorithm. Yet, aren’t the chemical and electrical impulses in our own human brains performing the same function, somehow conceived as “organic” in their creation because we did not manipulate the original construction? These are the questions that the film flirts with; what is the difference between “organic” and “mechanical”. If you want to explore these questions more, they are at the core of the recently ended Battlestar Galactica television series…

2.

“DAVID

Mommy, if Pinocchio became a real boy and I become a real boy can I come home?

MONICA

But that’s just a story, David.

DAVID

But a story tells what happens!

MONICA

Stories are not real! You’re not real!”

The nature of storytelling. My favorite films have this as an underlying theme; presenting a story itself, while questioning the purpose of such a thing is a difficult tightrope to walk (a recent example, a failure in terms of direction perhaps, might be Lady in the Water; a recent pinnacle of this sort would, of course, be Mulholland Dr.). Kubrick is using the shell of the Pinocchio story, a well-known fairy tale that spans various cultures to provide a basis of familiarity, and expanding upon it to fit a current need. The piece of dialogue above is crucial. It is the part where I tear up at the masterful simplicity at which this particular story distills all of human art(ifice) into a single exchange. Stories are real, because we created them out of the world. The world is, in turn, perceived as a story, forever changing, forever updating, forever behind us.

There are lots of literary precedents I could point to, from Bruno Bettelheim to Joseph Campbell (who George Lucas, and certainly Spielberg as his close collaborator and friend, is well-known to have perused in the creation of Star Wars). But doing this in film is a rare thing (so far, anyway). Most stories are presented as ‘not real’; as escapist fantasy for us all to hypnotize ourselves away from what we define as the Real. We both make the distinction and continue to seek out the difference to stay sane (and entertained in our existence). Combining the two is the definition of intellectual. I’m not trying to be pretentious or laudatory when I state that this story is an example of ‘intellectual filmmaking’. It simply defines itself. The peculiarity of this film, however, is in how it so visibly struggles with itself to maintain this dichotomy; it is both story entertainment in the clearest of Spielbergian grammar and story reflexive in its groundings in the genre of science-fiction/fantasy. The combination of this manipulation of emotion of its audience and the unfolding of ideas is key to defining a piece of art as “relevant”, or some may argue, as simply defining it as “art” in the first place. Is what we feel real or imagined when we experience a piece of art? Are we viewing the film as a piece detached from reality, aware of our own separateness or Are we applying the ideas to our own existence, participating in its creation for us as an individual? These are the questions that define my devotion to Art(ifice) as a guide through life. It is best way how I can describe why I love movies (and books and anything that ‘tells a story’).

3.

“JOE

“JOE

She [MONICA/MOMMY] loves what you do for her, as my customers love what it is I do for them. But she does not love you David, she cannot love you. You are neither flesh, nor blood. You are not a dog, a cat or a canary. You were designed and built specific, like the rest of us. And you are alone now only because they tired of you, or replaced you with a younger model, or were displeased with something you said, or broke. They made us too smart, too quick, and too many. We are suffering for the mistakes they made because when the end comes, all that will be left is us. That’s why they hate us, and that is why you must stay here, with me.

DAVID

Goodbye, Joe.”

And, as they say, here is the rub. Artifice, by definition, is not real. What we experience when we view a film, read a book, is usually seen as a temporary displacement, at worst a distraction, from our real, everyday lives. Yet, what we take from it, what we think and make of it, becomes part of our real lives, informing and creating what we individually define as real. This is where I could quote Jean Baudrillard and possibly stoop to referencing The Matrix, which is basically the filmed example of his Simulacra and Simulation (or the parts I could understand anyway). Whose to say what we do in our real lives is any less artificial, especially these days in our much more intimate melding with (virtual) technology? I’m not suggesting we live in a literal “Matrix” (I’m not that cracked), but emotionally, most of our lives (or maybe it’s just me?) are surrounded by stimuli that have no barring on our interaction with individual human beings. Our dispersal of cultural viewpoints and endless amount of specialized, perhaps trivial, knowledge does nothing to connect us in communicating with another, real, live person. Or are we all so inundated with this artificiality, that it has become our connection with others? Joe presents a rather similarly bleak view of the world in the piece of dialogue above. He’s talking about the difference between he and David being mechanical robots and humans being something else; Us and Them, but he could just as easily be talking about the difference between human generations (like say the digital divide between Baby Boomers and their kids).

A challenging thought: when all is defined by our perception of the world through the story we’ve created for it to be, then isn’t the Real, by definition, the ultimate human Art?

Metaphysical rant (and boring vacation) over.